Bestselling British author C.S. Lewis wrote more than 30 books of fiction and non-fiction. With estimated sales approaching 200 million copies in print, Lewis (1898-1963) is best-known for his children’s fantasy series The Chronicles of Narnia and his devilish epistolary novel The Screwtape Letters.

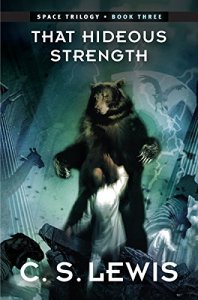

Lewis also wrote science fiction – most notably, his Space Trilogy, which culminates with That Hideous Strength, Lewis’ most libertarian novel.

Lewis also wrote science fiction – most notably, his Space Trilogy, which culminates with That Hideous Strength, Lewis’ most libertarian novel.

Selected by LFS judges as one of this year’s Prometheus Hall of Fame finalists for Best Classic Fiction, That Hideous Strength offers a dystopian and metaphysical vision that dramatizes warring ideologies of good and evil, freedom and tyranny.

Each novel in the Space trilogy (also known as the Ransom trilogy) is set on a different planet with Book One, Out of the Silent Planet, taking place on Mars; and Book Two, Perelandra, on Venus.

A CAUTIONARY TALE, MYSTERY AND ARTHURIAN FANTASY

Set on Earth, That Hideous Strength works as both a cautionary tale and a mystery as hidden powers scheme to enslave humanity.

Initially focused on the academic politics of a musty college in mid-20th-century England but expanding into Arthurian fantasy, Satanic conspiracies and cosmic/theological themes, the story exposes layer after layer of diabolical deception as double-talking, self-seeking professors and corrupt bureaucrats promote a rising progressive-left ideology that seeks absolute power.

As LFS President William H. Stoddard, who chairs the Prometheus Hall of Fame judging committee, has observed, Lewis “does an excellent job of showing how the shift from law, which viewed people as acting subjects, to planning, which views them as acted-upon objects, destroys the rationale for a free society — and ultimately destroys the very planners themselves.”

Cambridge philologist Elwin Ransom, the main character in the previous novels in the trilogy, continues as a major character in the third. Also known as the Pedestrian, Ransom directs an organization resisting the demonic takeover of the world. A mentor to others, Ransom ultimately becomes a saint-like Prophet.

A HUSBAND AND WIFE, DIVIDED IN BATTLE

A HUSBAND AND WIFE, DIVIDED IN BATTLE

At the center of the novel are Jane and Mark Studdock, stuck in a relatively new and loveless marriage. Mark, a sociologist, and Jane, an aspiring literary scholar, become enmeshed with a powerful but mysterious organization known as N.I.C.E. (National Institute of Coordinated Experiments) that aims to establish a major new facility on campus.

Jane, who’s given up writing her PhD. paper on John Donne to become a dissatisfied housewife, begins to question her own sanity after having a series of dreams about the severed head of a scientist, Alcasan.

Mark, meanwhile, is an ambitious professor obsessed with reaching the inner circle of his academic caste. Yet his shaky progress in climbing the rungs of N.I.C.E. actually becomes a descent into hell.

The result is that the husband and wife unexpectedly wind up on opposing sides of a deepening battle between spiritually based Natural Law, reflecting the rhythms and decency of everyday life, and the insidious spirit-denying falsehoods of Logical Positivism (an influential mid-century philosophy that Lewis believed was seriously flawed, with civilization-threatening implications).

As he’s drawn deeper into the sinister organization, Mark discovers that his wife’s dreams are real when he meets the literal head of Alcasan, kept alive for nefarious purposes by infusions of blood. Animated in a totemic fashion, the head seems symbolic of Lewis’ Christian perspective on the warped idealism of authoritarian progressives who view people as minds without souls.

A CHAMPION OF LOVE, LIBERTY AND DECENCY

As an alternative to such monstrosities, Lewis champions love, marriage and the basic decency of humanity, struggling to live and live up to age-old Christian ideals even amidst the perennial temptations of power, wishful thinking and other age-old human flaws.

Amidst its dramatic arc of demonic corruption and angelic redemption, Lewis’ novel explores mid-20th-century intellectual and political trends to warn about the dangers of a centrally planned pseudo-scientific and Nazi-like society literally hell-bent on controlling all human life.

Lewis depicts the people of England under growing threat by abusive instruments of State power, noting “their houses had been taken from them, their livelihood destroyed, and their liberties threatened by the Institutional Police.”

Published in 1945, and written at the peaks of collectivism in Europe and Russia, That Hideous Strength offered a timely warning about the insidious ways that rising totalitarianism of the Left or Right deadens the human spirit and denies reality, liberty and true morality.

In the foreword to the first edition, Lewis drew explicit parallels between the themes of his novel and The Abolition of Man, perhaps his non-fiction book that is most consistently proto-libertarian.

In both books, Lewis upheld objective values of good and evil and advocated recognition of natural laws and truth as a moral and spiritual bulwark against evil, error, delusion and the subjectivist denial of reality that tends to corrupt human relationships under all dictatorships.

His foundational Christian and protolibertarian view, only belatedly grasped by one central character: “… that souls and personal responsibility existed.”

A CRITIQUE OF SCIENTISM AND THE THERAPEUTIC STATE

Lewis’ concerns about the early rise of the therapeutic state and his critique of modernism, progressivism, the “strong man” ideologies of fascism/socialism and the dangers of scientism (science not as the value-free pursuit of truth, but as an elitist justification for social control) seem prescient today.

Incorporating many of the same insights that fellow Brit George Orwell would dramatize just three years later in Nineteen Eighty-Four, Lewis dramatizes how any form of tyranny – including what Orwell called the “smelly little orthodoxies” of the Left – undermine honesty, integrity, decency, morality, objectivity, the pursuit of knowledge and truth itself.

Especially impressive dramatically is Lewis’ slow uncovering of the layers of evil, many cloaked within evasive academic double-talk and polite euphemism. Such radical subjectivism and outright denialism of objective reality is so pervasive that in response to Mark Studdock’s queries, one yearns for the corrupted academics and bureaucrats to reply just once with an unambiguous “yes” or “no.”

As Stoddard observed, the novel ultimately offers not only an insightful dissection of evil but redeemingly, a powerful statement about love and Charity, which Lewis calls “fiery, sharp, bright and ruthless . . .”

Reflecting his deep views as perhaps the leading Christian philosopher-artist of the 20th century, the positive alternative Lewis envisions is a reaffirmation of spiritual decency and common humanity as individuals act voluntarily and benevolently towards each other to sustain a community where “all men are brothers (under God).”

A CLASSIC OF ITS ERA, WITH FLAWS OF ITS ERA

Although Lewis invests the novel with some humor, That Hideous Strength is often dry in style and somewhat uneven in writing.

Sadly, some aspects not only seem dated but have become offensive – especially in the crude stereotyping of its only female villain.

A butch lesbian nicknamed “The Fairy,” Miss Hardcastle heads the N.I.C.E. private police force, which engages in police brutality. Lusting after female prisoners and getting sexual pleasure from abusing them, Hardcastle leads a plot to incite riots to pressure the government to grant N.I.C.E. emergency powers. Aren’t her actions evil enough without implying that her very sexuality is inherently corrupt and perverted – prejudiced views common in the 1940s but understood to be false today?

Even with such defects, the novel remains worth reading.

Evoking a police state in the takeover of a local village and warning about the dangers of bureaucracy, Lewis seems most prophetic today in his cautions about the therapeutic state and the rising ideology of scientism.

THE SPIRITUAL WAR AT THE NOVEL’S HEART

Towards its conclusion, the novel incorporates increasingly mystical elements, including bringing Merlin himself into the 20th century for a final apocalyptic confrontation between good and evil.

Towards its conclusion, the novel incorporates increasingly mystical elements, including bringing Merlin himself into the 20th century for a final apocalyptic confrontation between good and evil.

The context of the spiritual battle in That Hideous Strength is set up by the previous novels in the Space Trilogy, as Stoddard noted in his nominating statement. When some people from Earth traveled to Mars, they inadvertently broke the barrier between sublunary and superlunary space, allowing the angels of the other planets to gain access to Earth, whose own angel is fallen and corrupt.

Even as That Hideous Strength provides a satisfying resolution to the Space Trilogy, it works well enough as a stand-alone novel. In some ways, it’s more plausibly and vividly imagined than Out of the Silent Planet and Perelandra, since Lewis was very familiar with real-world academia and bureaucracy from his years at Oxford.

WHY LEWIS RANKS WITH OTHER BRITISH DYSTOPIAN AUTHORS

With its darker focus on the grim consequences of a growing tyranny and evil on Earth, the novel fits well into the landscape of other British dystopian classics – including such Prometheus Hall of Fame winners as Orwell’s Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four and Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange. Like these other classics, That Hideous Strength warns about the dangers of communism, fascism and national socialism – all the rising statist and collectivist ideologies that were threatening the lives and liberties of millions in Lewis’ mid-20th-century era.

As reflected in its deus ex machina ending, Lewis’ alternative ideal is a religion-inspired community of goodness, love and sacrifice and mutual respect drawing on the norms of basic human decency that have evolved and matured over the centuries.

As Jessica Hooten Wilson writes insightfully in her essay on “Three Dangerous Philosophical Novels” (published in Faith & Culture, The Journal of the Augustine Institute), “Against what one character calls ‘goodness in the abstract,’ which produces ‘the fatal idea of something standardized—some common kind of life to which all nations ought to progress,’ That Hideous Strength uplifts the virtue of particular persons enacting grace toward one another.”

Prometheus-winning novelists J. Neil Schulman (The Rainbow Cadenza) and Brad Linaweaver (Moon of Ice), huge fans of Lewis’ fiction and non-fiction and sadly now both passed, were greatly influenced by his thinking and considered Lewis the greatest Christian libertarian of the 20th century.

Just as The Abolition of Man arguably comes closest in Lewis’ nonfiction to making Lewis’ protolibertarian sensibilities explicit a generation or two before the emergence of modern full-fledged libertarianism, That Hideous Strength is the fictional work that best makes clear Lewis’ profound love of both liberty and humanity under God.

Just as The Abolition of Man arguably comes closest in Lewis’ nonfiction to making Lewis’ protolibertarian sensibilities explicit a generation or two before the emergence of modern full-fledged libertarianism, That Hideous Strength is the fictional work that best makes clear Lewis’ profound love of both liberty and humanity under God.

FOR FURTHER READING

* See former Prometheus editor Anders Monsen’s column “The Joyous Surprise of C.S. Lewis’s Mundane SF Novel,” which hails That Hideous Strength as “a well-written and nearly timeless work of fiction” and concludes that “certainly, there are pro-liberty sentiments in the book, or at the very least anti-statist views. Much like the socialists that Friedrich Hayek denounced many times over for their planners’ conceit, we see the same experimental sociology denounced by Lewis, in quite a convincing fashion.”

THE PROMETHEUS HALL OF FAME FINALISTS

Along with Lewis’ That Hideous Strength, four other works have been selected this year by LFS judges as finalists for the 2026 Prometheus Hall of Fame for Best Classic Fiction. Reviews of all finalists have now been published on the Prometheus Blog: The Star Dwellers, a 1961 novel by James Blish; Brave New World, a 1932 novel by Aldous Huxley; Salt, a 2000 novel by Adam Roberts, and Singularity Sky, a 2003 novel by Charles Stross.

Meanwhile, capsule descriptions of each finalist are included in the LFS Hall of Fame finalist press release, which was announced in full on File 770.

ABOUT THE PROMETHEUS AWARDS AND THE LFS

* Join us! To help sustain the Prometheus Awards and support a cultural and literary strategy to appreciate and honor freedom-loving fiction, join the Libertarian Futurist Society, a non-profit all-volunteer international association of freedom-loving sf/fantasy fans.

Libertarian futurists understand that culture matters. We believe that literature and the arts can be vital in envisioning a freer and better future. In some ways, culture can be even more influential and powerful than politics in the long run, by imagining better visions of the future incorporating peace, prosperity, progress, tolerance, justice, positive social change, and mutual respect for each other’s rights, human dignity, individuality and peaceful choices.

* Prometheus winners: For a full list of Prometheus winners, finalists and nominees – including in the annual Best Novel and Best Classic Fiction (Hall of Fame) categories and occasional Special Awards – visit the enhanced Prometheus Awards page on the LFS website. This page includes convenient links to all published essay-reviews in our Appreciation series explaining why each of more than 100 past winners since 1979 fits the awards’ distinctive dual focus on both quality and liberty.

* Watch videos of past Prometheus Awards ceremonies, Libertarian Futurist Society panel discussions with noted sf authors and leading libertarian writers, and other LFS programs on the Prometheus Blog’s Video page.

* Read “The Libertarian History of Science Fiction,” an essay in the international magazine Quillette that favorably highlights the Prometheus Awards, the Libertarian Futurist Society and the significant element of libertarian sf/fantasy in the evolution of the modern genre.

- Check out the Libertarian Futurist Society’s Facebook page for comments, updates and links to the latest Prometheus Blog posts.

Lewis talks about this in “Men without Chests,” where he places the mind in the head, the body in the belly, and the soul, or perhaps the spirit, in the chest (logical in that spirit = breath etymologically, but also linked perhaps to the heart). It seems as if he regards soul/spirit as the middle term.